The National Democratic Congress (NDC) has proposed an ambitious policy aimed at transforming Ghana into a 24-hour economy. The underlying assumption is that extending business hours across sectors—whether in retail, services, or public infrastructure—will boost productivity, create jobs, and stimulate growth. While the policy is novel in the context of Ghana’s current economic situation, historical and empirical evidence from other countries provides an important framework for assessing its potential success.

In particular, the development trajectories of Singapore, Malaysia, and South Korea offer valuable lessons. These nations were once as poor as Ghana at the time of independence in 1957 but managed to leap into upper-middle or high-income status within a few decades. Analyzing how they achieved such rapid transformation reveals that while economic policies aimed at boosting productivity—like the NDC’s 24-hour economy proposal—can contribute to growth, they are more likely to succeed with investments in education, infrastructure, governance, and technological innovation.

A 24-hour economy seeks to expand economic activities beyond traditional business hours, effectively creating a non-stop commercial ecosystem. By doing so, the theory suggests that countries can extract more productivity from available resources, reduce urban congestion, and provide greater access to services for citizens. Proponents of this commendable NDC policy argue that sectors such as transportation, logistics, retail, and manufacturing can benefit significantly from round-the-clock operations, improving competitiveness and creating more jobs.

However, while a 24-hour economy sounds appealing in theory, its success depends on several underlying factors. Infrastructure, energy supply, governance, and human capital must be sufficiently developed to support such an ambitious policy. To better understand these prerequisites, it is important to examine the development strategies that propelled Singapore, Malaysia, and South Korea from poverty to prosperity. Their success stories offer insights that could inform the successful implementation of a 24-hour economy in Ghana.

Singapore

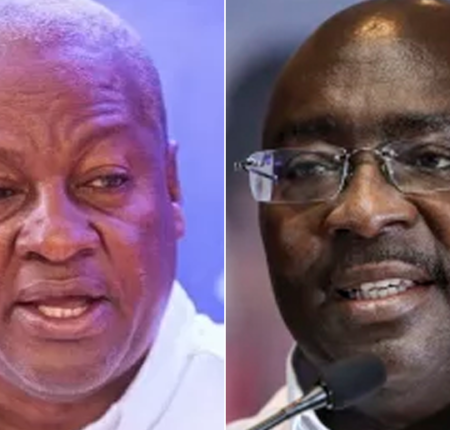

Singapore’s development story is a testament to how visionary leadership and a focus on human capital can transform a country’s fortunes. In the 1950s, Singapore was a small island grappling with limited resources and deep poverty, similar to Ghana at the time. However, under the leadership of Lee Kuan Yew, Singapore embarked on a path of strategic development that emphasized good governance, meritocracy, and effective urban management. The government invested heavily in education and healthcare, understanding that human capital was a fundamental driver of long-term economic growth (Lee, 2000). For Ghana, the visionary leadership offered by the NDC’s President John Mahama in developing education, health, energy, and transport infrastructure during his previous term as president makes him trustworthy to deliver again.

Key to Singapore’s growth was its integration into global markets. Singapore positioned itself as a hub for trade, finance, and logistics, attracting foreign direct investment (FDI) by ensuring political stability and creating a pro-business environment. Singapore’s government also promoted efficiency by modernizing its infrastructure and maintaining a highly reliable power grid and transportation system (Huff, 1994).

In the case of Ghana, the path to a 24-hour economy would require not only extended working hours but also substantial improvements in human capital and infrastructure. Singapore’s success was not merely about productivity; it was about enabling productivity through strategic planning and investment in people. Without similar investments, Ghana’s efforts to create a 24-hour economy may face limitations, especially given the existing challenges in energy supply and labour market regulations. This is why the previous NDC government under President John Mahama expanded energy infrastructure; resolved the energy crisis popularly called “dumsor” by 2015; and set up the Energy Sector Recovery Levy (ESLA) fund now depleted and mismanaged by the NPP government.

Malaysia

Like Ghana, Malaysia in the 1950s was heavily dependent on commodity exports, particularly rubber and tin. However, Malaysia’s economic diversification efforts set it on a course toward industrialization and export-oriented manufacturing. The government implemented policies that promoted industrialization, initially focusing on light industries such as textiles and gradually moving towards heavy industries such as electronics and petrochemicals. This diversification was facilitated by significant investment in infrastructure, including transportation, energy, and telecommunications (Rasiah, 2011).

Malaysia’s rapid economic growth also benefited from its strategic location, political stability, and well-developed institutions. It established industrial parks, improved logistics networks, and invested in human capital, all of which made it easier for the private sector to thrive (Jomo, 1997). These improvements laid the foundation for a more diversified economy that could sustain growth even as commodity prices fluctuated.

Ghana adopting a 24-hour economy would necessitate a similar focus on industrial diversification and infrastructure development. Ghana’s economy remains largely dependent on natural resources like cocoa, gold, and oil, making it vulnerable to global price fluctuations. To sustain a 24-hour economy, Ghana would need to diversify into manufacturing and other value-added sectors while upgrading its infrastructure to ensure reliable power and transportation for businesses operating round the clock. These development plans are outlined in the NDC 2024 manifesto.

South Korea

South Korea’s rise from one of the poorest countries in the 1950s to one of the most technologically advanced economies today offers critical insights for Ghana. South Korea adopted an export-driven industrialization strategy, focusing on sectors such as electronics, automobiles, and shipbuilding. The South Korean government, working closely with large conglomerates known as chaebols, provided financial incentives, subsidies, and R&D support to drive industrial growth (Amsden, 1989).

Key to South Korea’s success was its heavy investment in technological advancement. The government prioritized education and innovation, establishing world-class research institutions and universities that became drivers of new technologies and industries. This emphasis on innovation allowed South Korea to move up the value chain, from producing low-cost goods to creating high-tech products with significant global demand (Kim, 1997).

For Ghana to successfully transition into a 24-hour economy, it must focus on similar strategies of export-driven industrialization and technology-led growth. The country’s reliance on low-value-added commodities must give way to a diversified industrial base, supported by innovation and technological advancement. Additionally, South Korea’s work culture, characterized by long working hours and a focus on productivity, provides a model for the cultural shifts that may accompany a 24-hour economy. However, such a model must be adapted to Ghana’s labour market, ensuring that increased working hours do not lead to worker exploitation.

While Ghana can learn valuable lessons from East Asia, it is essential to consider the unique challenges and opportunities within the African context. Ghana’s informal sector, which accounts for over 80% of total employment, presents a significant challenge to the formalization of a 24-hour economy. In contrast, Singapore, Malaysia, and South Korea benefitted from having more structured economies with a strong manufacturing base and a clear path toward formalization.

Moreover, Ghana’s energy sector remains underdeveloped and badly mismanaged by the Bawumia-Akufo Addo NPP government, with frequent power outages and high costs of electricity (World Bank, 2020). This contrasts sharply with the reliable infrastructure that supported Singapore’s and South Korea’s industrial expansion. Without consistent and affordable power supply, businesses may be unable to operate efficiently, rendering a 24-hour economy unsustainable.

There are opportunities unique to Ghana. The country’s strategic location within West Africa and its positioning as a gateway to the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) could make it a hub for logistics and trade. Additionally, sectors such as tourism, retail, and fintech could benefit from a 24-hour economy if supported by robust digital infrastructure and governance frameworks that facilitate ease of doing business.

The NDC manifesto proposal to create a 24-hour economy therefore presents a bold vision for economic transformation. As the experiences of Singapore, Malaysia, and South Korea demonstrate, such a policy must be grounded in broader reforms. This is why the NDC promises substantial investments in education, infrastructure, human capital, and technology, as well as efforts to diversify the economy and attract foreign investment.

The 24-hour economy policy can serve as a catalyst for growth, and the NDC is fully aware that the policy stands a better chance of success when the next government simultaneously addresses the underlying structural challenges facing Ghana—such as its dependence on commodities, weak infrastructure, and the large informal sector—to ensure the policy does not fall short of its ambitious goals. Learning from the successful strategies of East Asia, Ghana under President John Mahama would chart a new path toward sustainable and inclusive development.

Author:

Prince Kassim Senaya Alubankudi, MBA

Policy Analyst and Fellow at UPDI Africa & International Business Consultant

www.updiafrica.com